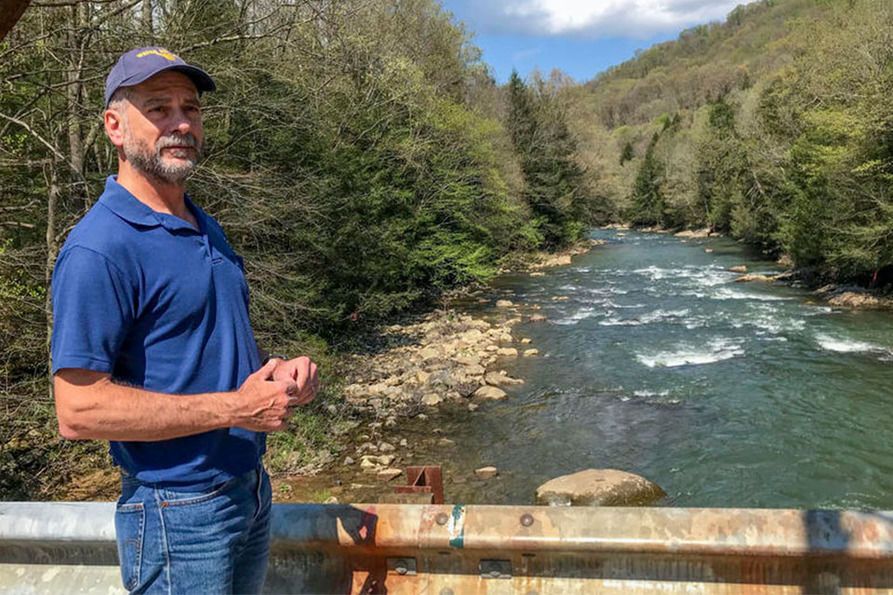

Paul Ziemkiewicz, director of the West Virginia Water Research Institute at WVU, on a bridge overlooking Big Sandy Creek. Photo by Brittany Patterson, West Virginia Public Broadcasting

Story by Brittany Patterson, West Virginia Public Broadcasting

On a recent sunny Wednesday, Paul Ziemkiewicz, director of the West Virginia Water Research Institute at West Virginia University, was standing on a bridge looking out at Big Sandy Creek. It was a balmy afternoon, perfect for kayaking, and the creek running the Cheat River was clear. But 25 years ago, this water was a shocking orange color -- from acid mine drainage.

"Look at this," Ziemkiewicz said, gesturing to the raging water below. "This is a fishery now, but it was completely dead back then."

This year the last heavily-polluted stretch of of the watershed is set to be cleaned up.

"In my lifetime a river that was dead has now come back," said Amanda Pitzer, executive

director of Friends of the Cheat, a local conservation group that was formed

by a motley crew of river guides and enthusiasts in 1994 to deal with acid mine

pollution. The group also hosts the annual Cheat River Festival to celebrate

the river and raise money to restore it.

Ziemkiewicz said originally in the Cheat River watershed -- as is the case in many places dealing with AMD across Appalachia -- regulators tried to address the problem by treating each individual mine contributing pollution to the river. But it’s not always effective.

"You can throw almost infinite amounts of money trying to treat point sources like that in a watershed like this that has both abandoned mines and also bond forfeiture sites and not make any impact at all on the quality of the stream because the abandoned mines dominate the whole picture," he said.

A key piece to making this new approach work was some innovative thinking on the part of state regulators. The state DEP created an alternative clean water permit, which allowed the agency to address streamwide water quality, rather than treat individual pollution sources.

"The watershed scale strategy that DEP is using here actually restores the creek and for a lot less money," Ziemkiewicz said.

Part of a passive treatment system at Sovern site No. 62. Photo by Brittany Patterson, West Virginia Public Broadcasting.

Standing in a grassy clearing overlooking this forested valley, it’s just possible to see the entry to a now-abandoned coal mine here in the headwaters of Sovern Run, a tributary of Big Sandy Creek, which runs into the Cheat.

Ziemkiewicz and his team built what’s called a "passive treatment" system. At Sovern site No. 62, AMD pollution flows through a series of limestone-lined ponds and channels. The alkaline limestone turns low pH, acid water coming out of the mine into much cleaner water through naturally-occurring chemical reactions. Passive systems don’t require power or the addition of chemicals and are often lower maintenance.

"We were able to knock off something like 80 percent of the acid load, most of the iron," Ziemkiewicz said, of the passive treatment system. "The idea was to put a lot of these all over the watershed."

-WRI-